[ каталог выставки ]

[ каталог выставки ]

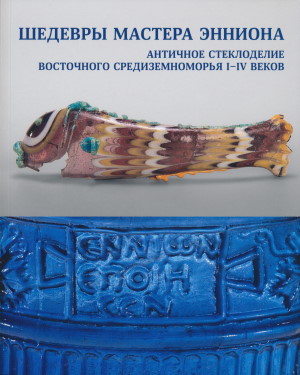

Шедевры мастера Энниона.

Античное стеклоделие Восточного Средиземноморья I-IV вв.

/ Каталог выставки. СПб: Изд-во Гос. Эрмитажа. 2021. 224 с. ISBN 978-5-93572-949-3

Каталог выставки в Государственном Эрмитаже,

Санкт-Петербург, 3 декабря 2021 г. – 13 марта 2022 г.

[ аннотация: ]

Каталог выставки «Шедевры мастера Энниона. Античное стеклоделие Восточного Средиземноморья I-IV вв.» включает 90 разнообразных произведений этого древнего художественного ремесла. Помимо общих сведений об источниках поступления предметов в собрание Эрмитажа в публикации рассказывается об известном израильском коллекционере Шломо Муссайеффе, вдова которого, Алиса Муссайефф, предоставила для выставки четыре стеклянных сосуда работы Энниона, прославленного античного стеклодела, чья мастерская функционировала в римской провинции Сирия в первой половине I в. Важнейшим украшением экспозиции стал созданный Эннионом великолепный кувшин синего стекла из Музея МУЗА Эретц Исраэль (Тель-Авив). Большая часть включённых в выставку изделий из стекла, 83 предмета, хранится в эрмитажном собрании.

Из каталога можно узнать об истории античного стеклоделия, о том, что известно об Эннионе, о различных техниках, в которых работали древние мастера, создавшие стеклянные сосуды, дошедшие до нас через тысячелетия, и об отдельных сюжетах, которые их привлекали. Специальная статья посвящена жившему в Одессе Юлиусу Христиановичу Лемме, крупнейшему коллекционеру второй половины XIX в., из собрания которого в Эрмитаж поступил ряд ценных экспонатов, представленных на выставке.

Каталог адресован широкому кругу читателей, интересующихся историей и искусством.

Содержание

Е.Н. Ходза. Введение. — 12

Е.Н. Ходза. Из истории античного стеклоделия. — 21

О.В. Горская. Античное стекло из коллекции Ю.Х. Лемме в собрании Эрмитажа. — 65

Каталог. — 81

[Пояснения к каталогу. — 82]

Техника сердечника [кат. 1]. — 85

Техника литья и прессовки [кат. 2-6]. — 87

Мозаичная техника [кат. 7]. — 92

Техника выдувания в матрице [кат. 8-48]. — 93

Техника свободного выдувания [кат. 49-90]. — 157

Приложение [Формы античных сосудов]. — 206

Принятые сокращения. — 209

Литература. — 209

Прочие. — 215

[Иллюстрации предоставлены… — 223]

От Сидона до Пантикапея. ^

Он жил в Сидоне (Сайде) в I веке нашей эры, производил и продавал по всему римскому миру знаменитые стеклянные сосуды тонкой работы и был одним из первых, кто стал выдувать стекло в формы – матрицы. Его звали Эннион; своё имя в формуле «Эннион делал» и «Эннион сделал это» он размещал в виде «таблички с ручками» среди узоров своих же изделий.

Умелый дизайн «торговой марки» и копирайта сделал его самым знаменитым творцом античного стекла. Эрмитаж гордится его произведением – изящной амфорой оттенка тёмного янтаря с узорами из виноградных побегов и пчелиных сот. Она была найдена в ХIX веке в некрополе Пантикапея, знаменитом памятнике античной культуры в Северном Причерноморье, откуда происходит значительная часть нашей коллекции римского стекла. Такие изящные сосуды служили для хранения и транспортировки драгоценных жидкостей – ароматических бальзамов, благовонных масел.

Это были аксессуары «красивой жизни», роскоши. Их ценили, берегли и собирали во все времена любители прекрасного, такие как знаменитый коллекционер и глава ювелирной империи Шломо Мусаев, четыре шедевра из коллекции которого стали поводом для этой выставки. К ним присоединился прекрасный «Синий кувшин» из Музея Эретц Исраэль в Тель-Авиве. Они составили «свиту» нашему сосуду, а вокруг них водят хоровод замечательные разнообразные предметы из нашей собственной коллекции, среди которых есть и произведения мастерской и учеников Энниона. Такая выставка с именами и гостями позволила по-новому показать эрмитажное собрание римского стекла, которое богато и внушительно, но иногда теряется в «скучных» витринах постоянной экспозиции. Там много замечательного, в том числе и символы земли, с которой происходят работы Энниона, – сосуды в виде сушёных фиников и экзотичных средиземноморских рыб.

Получился праздник стекла, волшебного материала, рождённого из песка и соперничающего с драгоценными камнями глубиной цвета и света. Соперничество это усилилось, когда стекло научились выдувать, делать его тонким и способным по-особому преломлять свет на поверхности и в содержимом сосуда. Драгоценные камни замечательны своей твёрдостью, но хрупкость стекла делает его как бы более нежным, редким, трудным к транспортировке и потому исключительным.

Стекло составляет важную часть облика Эрмитажа. Это – «фиолетовые» стёкла на окнах и огромные стеклянные торшеры, изящные мозаичные столы и звонкие подвески на люстрах. Это – громадные коллекции искусства стекла – римского, византийского, исламского, русского, западноевропейского, современного. Недавно завершилась эффектная выставка «Стекло, которым любовались», с успехом открылась выставка «Гласстресс», где со стеклом экспериментируют гранды современного искусства от Ай Вэйвэя до Кабакова. Эрмитаж знаменит своими исследованиями по истории и эстетике стекла. Музейные реставраторы возвращают к жизни найденные нашими археологами античные творения стеклянных дел мастеров, таких как Эннион, умело создавшего заслуженный им «бренд».

Михаил Пиотровский,

генеральный директор Государственного Эрмитажа.

Summary. ^

The exhibition is devoted to the art of ancient glassmakers, active in the first – fourth centuries A.D. in the Eastern Mediterranean, a historical region spanning the territories of present-day Syria, Palestine, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Cyprus, which collectively formed part of a vast eastern province of the Roman Empire known as Roman Syria. Ancient written sources tell us that it was here that developments of paramount importance took place that revolutionised the history of glassmaking: around mid-first century B.C. local artisans discovered a technique for producing clear, transparent glass and started using a blowpipe to make glass wares. Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.), a Roman scientist and encyclopedist, points out that it happened in Phoenicia – a country stretching along a narrow strip of land on the eastern Mediterranean coast. In 64 B.C. Phoenicia was incorporated into Roman Syria.

A number of glass workshops operated throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, where the major part of the State Hermitage collection of ancient glass numbering over 3,000 artefacts originated. Large part of these exhibits came from private collections; some were acquired through various antique collectors and dealers. No less importantly, a fair amount of glass vessels were discovered during decades-long archaeological excavations, still ongoing, at the sites of the ancient cities of the Northern Black Sea Region – most prominently, the necropolis of ancient Panticapaeum, the capital of the Bosporan Kingdom (modern-day Kerch).

The first century has been chosen as the chronological starting point of the exhibition, as it best demonstrates the diversity of ancient glassmaking techniques that co-existed at a given time in history: namely, a core-formed technique, a cast and pressed technique, a mosaic technique, a freeblown technique and a mould-blown technique. The first of these, a core-formed technique, which was at its height in the sixth – fifth century B.C., had become virtually obsolete by that time. An amphoriskos, displayed in the first showcase, provides some insight into the texture of the glass mass, still opaque, as well as the distinctive ornamental designs and the colour scheme of such vessels. The second technique, which is believed to have been borrowed from artisans working with precious metals, experienced its heyday as early as during the Hellenistic period and was on the decline in the first century A.D. Yet, exquisitely crafted kantharoi, skyphoi and multi-coloured ribbed bowls, cast entirely in a mould, still feature prominently in the art of glassmaking in the first century A.D. In this regard, a female head made of transparent aquamarine glass – possibly, a portrait of the Roman Empress Livia – is a particularly noteworthy exhibit.

The mosaic technique, by contrast, flourished at that time and enjoyed immense popularity among craftsmen. A rather sophisticated and labour-intensive process that encompassed several stages, this technique offered a rich choice of colours and allowed to create eye-catching designs and imitate semiprecious stones or marble. Mosaic-type glassware was extremely expensive.

However, only the free-blown technique that involved the use of a blowpipe revealed the truly unique properties of glass – its transparency that allows light to pass through it and the ability of glass to hold the shape it was given while still hot and malleable after cooling. This technique, offering ample creative freedom to design jugs, chalices, bowls, perfume flasks and apothecary jars of every imaginable shape and form, has enjoyed the widest popularity since Antiquity and to this day. The main section of the exhibition focuses on glass wares made using the most complex and intricate glassblowing technique, the mould-blown technique. It was used to create amphorae, jugs or bowls with surfaces decorated with various relief patterns, sometimes consisting of only ornaments, other times bearing sculptural compositions,

(217/218)

occasionally combined with ornamental designs. The process began with producing a, most commonly, terracotta model of the future vessel with the desired shape and relief pattern. A clay mould was then made, which had these patterns incised in sunken relief. The mould was cut into separate parts and the model was removed. After baking, the mould parts were joined back together tightly to ensure a seamless fit. Next, a gob of glass was inflated into the matrix and, as the glass was forced against the inner surface of the mould, the designs carved therein were patterned onto the glass in relief. The matrix was then removed piece by piece and the vessel was fired in a furnace. Researchers have yet to figure out how ancient glassmakers managed to reassemble the detachable mould parts with such precision and then loosen them to pull out the glass object without damaging its shape and décor. The matrix could be reused to create a series of vessels that differed in certain details, such as the neck, the rim and handles or colour of the glass itself. Examples can be seen in the exhibition, which showcases rare glass vessels of exquisite workmanship alongside mass market wares.

The most skillful glass craftsmen, whose mastery of the mould-blowing technique was unrivalled in the region, came from the city of Sidon (present-day Sayda), located on the coast of Phoenicia (modern Lebanon). Wares produced in their workshops were greatly prized for their remarkable quality and were a coveted commodity among merchants – long-existing trade routes and convenience of the Sidon sea port facilitated export. The major maritime trade route, which led through Sidon, stretched from Egypt to Anatolia, Italy, Greece and further. It is no surprise, then, that mould-blown glass vessels of various shapes and sizes crafted by artisans of the Eastern Mediterranean using the mould-blown technique were discovered in many places across the vast Roman Empire, from Spain to Northern Europe and from Northern Europe to the Persian Gulf, reaching as far as the Northern Black Sea Region.

Of all the glassmakers who mastered the mould-blown technique, no one could rival a virtuoso named Ennion. His name has come down to us as part of the inscription that reads ‘Ennion made it’ or ‘Made by Ennion’. This inscription, always in Greek, is customarily enclosed in a special plaque, tabula ansata, and incorporated into an exquisitely refined ornament that decorates the surface of his amphorae and jugs. Most probably, he was a native of Sidon or its environs, where his workshop was located. Archaeological evidence provided by unearthed vessels bearing the famous glassmaker’s signature suggests that Ennion was born sometime between 27 B.C. and 14 A.D., during the reign of the Emperor Augustus, and lived about fifty years, based on the average life expectancy of a workman doing hard physical labour. The major point of contention regarding his biography, of which little else is known, is whether Ennion remained in the same place where began his career as a glassmaker or immigrated to northern Italy at some point and set up his own workshop there. Advocates of the latter view argue that a great number of bowls bearing Ennion’s ‘label’ were discovered in the north of Italy, which differ from his works unearthed in the East in shape and relief designs. Their opponents rebut with equally sound counterarguments. This dispute appears unlikely to ever be resolved fully.

Technical virtuosity and exceptional artistic value of Ennion’s vessels make them stand out as a shining accomplishment of ancient glassmaking. His wares were highly prized by contemporaries and were widely regarded as luxury items. The fact that Ennion incorporated his name into his vessels as a sign of authorship indicates that he himself recognised the remarkable value of his wares. The exhibition affords a chance to see six extraordinary glass vessels crafted by Ennion in a single visit. One of them is a unique amphora made of dark amber-coloured glass with a delicate floral ornament, discovered as far back as in 1852 in ancient Panticapaeum. Four other vessels of the finest workmanship – an amphora, a jug and two bowls – were loaned for this exhibition by Ms Alisa Moussaieff, the widow of a prominent collector, Shlomo Moussaieff. MUSA Eretz Israel Museum (Tel Aviv), loaned a magnificent jug of blue glass – the only jug made by Ennion that has survived completely intact.

|